A Union Man on the Strike

by George Brown

[George Brown was a well-known anarchist and labor activist in Philadelphia between 1893 and his death in 1915. Born in England in 1858, he was a shoemaker by trade.

This article appeared in the anarchist paper Free Society on Oct. 19, 1902, signed “George Brown of The U[nited] L[abor] L[eague], reprinted from the Philadelphia Public Ledger." – Ed.]

This article appeared in the anarchist paper Free Society on Oct. 19, 1902, signed “George Brown of The U[nited] L[abor] L[eague], reprinted from the Philadelphia Public Ledger." – Ed.]

It seems to me worthwhile to make a brief statement of the essential factors of the present strike problem. On the one side we have the coal trust, made up of a few men, who have complete ownership of the mines. They hold their title from the state through the law, which is the voice of the state. Their title is undisputed, and is legally perfect. It could not be interfered with without upsetting the whole institution of private property, and to do this would make a greater revolution than any that has taken place heretofore.

The State is under imperative obligation to protect these men in possession of their property, or it would cease to exist. For this reason the trust has a right to call on the State for effective protection, and if this should necessitate the shooting to death of every miner in the State, it would have to be done, and neither policeman nor soldier would be legally culpable. If the property rights of the trust are not maintained inviolate, then is no property safe? Neither is the trust under any obligation to arbitrate: why should it submit to arbitration what has already been settled in its favor? To import moral considerations into the matter is to make confusion. The trust is right legally, and all it has to do is insist that the law be carried out.

On the other side are the miners, 150,000 strong. They have no rights in the mine at all – not even the right to work – for the mine owners are not bound to employ anyone. There is, in fact, no such thing as a right to work. It is a privilege that may be granted or withheld as the employer sees fit, and if no employer sees fit, there is no power in the State to make him do so. If the opportunity to work is denied, the worker may go hang himself, for it is no part of the business of the State to see that he has work.

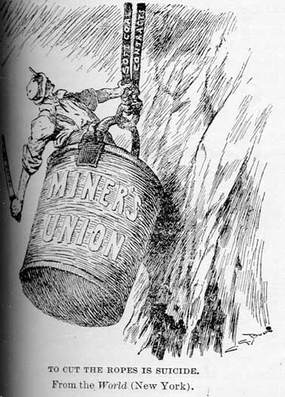

Seeing this, the more intelligent of the workers have come to look elsewhere for help, and have joined with their fellow workers into unions. These unions have never been legal. At first they were under the direct ban of the law, and were prosecuted as conspiracies, which they undoubtedly were. They grew in numbers and power, however, until they were, and are able to defy persecution, and so they have secured toleration. But they are not, even now, legal, and are not suppressed only because they cannot be. They may be properly described as extra-legal, being, in fact, secessions from the State, and they strive to gain their means by other than legal means.

Sometimes they do work for the enforcement of the so-called labor law, but most union men know well enough that labor legislation is a farce, and is only effective when a strong organization sees to its enforcement. And if a union is strong enough to enforce a law, it is strong enough to do without the law altogether. And so we find this miners’ union making this great fight for a decent living, not only without help from the State but with all the force of law and courts, as well as police and soldiery against them. For the union is an attack on property rights. It is a claim that human life is more sacred than property; that those who work have rights as deeply rooted as those who only manipulate them. The union man claims, too, that he has a right to a voice in deciding how and when the work should be done. Some of these points are for the future, for so long as there exists this law-made inequality, strikes will continue, no matter whether this one be won or lost. No one who has humane sympathies can for a moment accept present conditions as final. One word as to preventing the non-union man from working, to the injury of so many of his fellow men. Why does he not join the union and help in the common work of bettering conditions for all? He would be made welcome, and would find a greater measure of equality there than on the outside. He would have a voice and a vote on every question that came up, and if he proved himself able, he would rise to leadership, and be able to determine policies. What freedom would he lose by being a union man, other than the freedom to work for lower wages than his fellows? Are conditions outside the union so free and favorable that this is too great a sacrifice to make for the common good of all those who work?

The State is under imperative obligation to protect these men in possession of their property, or it would cease to exist. For this reason the trust has a right to call on the State for effective protection, and if this should necessitate the shooting to death of every miner in the State, it would have to be done, and neither policeman nor soldier would be legally culpable. If the property rights of the trust are not maintained inviolate, then is no property safe? Neither is the trust under any obligation to arbitrate: why should it submit to arbitration what has already been settled in its favor? To import moral considerations into the matter is to make confusion. The trust is right legally, and all it has to do is insist that the law be carried out.

On the other side are the miners, 150,000 strong. They have no rights in the mine at all – not even the right to work – for the mine owners are not bound to employ anyone. There is, in fact, no such thing as a right to work. It is a privilege that may be granted or withheld as the employer sees fit, and if no employer sees fit, there is no power in the State to make him do so. If the opportunity to work is denied, the worker may go hang himself, for it is no part of the business of the State to see that he has work.

Seeing this, the more intelligent of the workers have come to look elsewhere for help, and have joined with their fellow workers into unions. These unions have never been legal. At first they were under the direct ban of the law, and were prosecuted as conspiracies, which they undoubtedly were. They grew in numbers and power, however, until they were, and are able to defy persecution, and so they have secured toleration. But they are not, even now, legal, and are not suppressed only because they cannot be. They may be properly described as extra-legal, being, in fact, secessions from the State, and they strive to gain their means by other than legal means.

Sometimes they do work for the enforcement of the so-called labor law, but most union men know well enough that labor legislation is a farce, and is only effective when a strong organization sees to its enforcement. And if a union is strong enough to enforce a law, it is strong enough to do without the law altogether. And so we find this miners’ union making this great fight for a decent living, not only without help from the State but with all the force of law and courts, as well as police and soldiery against them. For the union is an attack on property rights. It is a claim that human life is more sacred than property; that those who work have rights as deeply rooted as those who only manipulate them. The union man claims, too, that he has a right to a voice in deciding how and when the work should be done. Some of these points are for the future, for so long as there exists this law-made inequality, strikes will continue, no matter whether this one be won or lost. No one who has humane sympathies can for a moment accept present conditions as final. One word as to preventing the non-union man from working, to the injury of so many of his fellow men. Why does he not join the union and help in the common work of bettering conditions for all? He would be made welcome, and would find a greater measure of equality there than on the outside. He would have a voice and a vote on every question that came up, and if he proved himself able, he would rise to leadership, and be able to determine policies. What freedom would he lose by being a union man, other than the freedom to work for lower wages than his fellows? Are conditions outside the union so free and favorable that this is too great a sacrifice to make for the common good of all those who work?