Ida Celanire Craddock & Voltairine de Cleyre: Two Freethinkers of Philadelphia

by Robert P. Helms

[This article was previously posted on the Bob Helms' Chin-Wag blog. - Ed.]

Ida C. Craddock (1857-1902) is one of countless radical figures whose lives are understood only partially by each interested party. However, Ida’s life is so compelling that scholars and researchers have never lost sight of that martyr of freethought. Presently, I will focus on the details of her life that I discovered, and on her interactions with Voltairine de Cleyre (1866-1912), Philadelphia’s celebrated anarchist and atheist. I will also share important details of de Cleyre’s life that I have uncovered over the years.

I write this article at a time when Ida Caddock is just beginning to be appreciated for the walking wonder she was during life. Starting with Theodore Schroeder, who collected a huge trove of Ida’s papers and other documentation during the ‘teens for a biography he never produced, through scattered articles over the decades, to Heaven’s Bride by Leigh Eric Schmidt (2010), this fascinating freethinker has caught the attention of many writers. However, each new researcher has fed the next. When, after knowing quite a lot about Ida for 15 years, I read Schmidt’s book, I was startled to find a photograph of her grave. I had not seen certain sources that informed the biography, so I had not located the grave. Early the next morning I walked one mile to Woodlands Cemetery and discovered something everyone else had missed: Ida’s middle name, which was Celanire. The family obelisk seems to be the only surviving document of this fact.

My delicious discovery of Ida’s middle name did not seem important, but a search of 19th Century literature determined that this Medieval French name almost never occurs, but “Celanire” is the author of eleven short sketches between March and July of 1879, the first in Potter’s American Monthly and the rest in the Saturday Evening Post. This is the only writer using the name in the English language during the 19th century, and both journals’ offices were closer to the 21-year old Ida’s home than my home is to her grave. I am pleased to share this connection as a certainty.

Ida Celanire Craddock was born in Philadelphia on August 1, 1857 as the only surviving child of Elizabeth “Lizzie” S. Craddock (later Decker), who remained the dominant force throughout the life of her brilliant daughter. Ida’s father was Joseph T. Craddock, who was previously married and widowed in 1852 with four children between ages nine and seventeen.

Lizzie entered the Craddock family around March, 1855 and gave birth to the first Ida Craddock at the end of that year. This Ida lived just seven months and was buried beside Joseph’s first wife, with no middle initial on the record. Lizzie’s second daughter, Ida C. Craddock, arrived thirteen months after her sister’s death. The first Ida re-emerges in the story later because she seems to become “Nana,” the spirit sibling who was important in Craddock’s mystical life.

Ida’s father died when she, his youngest child, was six months old. Three years later and just prior to the Civil War, Ida lived with her mother, her 20-year old stepsister Rebecca Craddock, and one servant. Rebecca married in 1864, so we can presume that Ida had an adult stepsister in her daily life until she was seven years old. However, Rebecca Craddock’s existence has been missed till now, along with much else I now share with the reader regarding the early life of Ida Craddock.

It has been repeated that both Ida’s parents were Quakers, but it was at a time when that religion was at its lowest level of activity in hundreds of years. Neither Ida nor her mother was recorded as a Quaker, and except in the fact that Ida attended the Friends Central School between ages sixteen and nineteen, and also she was involved in other Quaker-based activities (not scarce in Philadelphia) as the years passed. In one letter Ida mentions her “French blood,” and indeed Lizzie gave France as both her parents’ birthplace in the 1880 census. If this was a Quaker family, the Religious Society of Friends did not record it as such.

Previous writers have given sketchy information on Lizzie Decker’s later marriages, again because they overlooked the Brown Family plot at Woodlands Cemetery, which was created in November 1870 when the second husband James M. Brown died, and “L. S. Brown” lived at 1032-1034 Race Street with her 12-year old daughter Ida and one servant.

James M. Brown (c.1821, Ireland) was a produce merchant, listed as a gentleman from 1865, who lived at 1034 Race Street starting in 1867. We find no record of a marriage, but in his will, James left his entire estate to his wife, Elizabeth S. Brown, who was listed as his widow in the city directory for at least four years after his death. Lizzie was now a slightly rich, independent businesswoman.

Samuel B. Selvage (b. 1808, NJ) was a 72-year old retired merchant and a widower, in 1880. The younger of his two sons was a little older than Ida Craddock. From 1874 he was listed as a clerk, living at the medicine store on Race. Nine years later (1883), Selvage died and was buried alongside Mr. Brown. This old man may have been Lizzie’s husband, or her father, or just a boarder who became her friend and who could afford a proper grave. He leads us to the question, Where did Lizzie S. Decker come from, and what was her maiden name? If it was Selvage, we simply can’t place her.

Thomas B. Decker looks to be Lizzie’s last husband. From 1878 through 1886 he lived at 1034 Race, and Lizzie, who has by now gone from Craddock to Brown to Craddock again, takes on Decker as her final surname in 1880. But these entries in the city directory are the only reasons why we connect Thomas and Lizzie Decker at all. In 1879 only, there was also a boarder named Charles L. Decker at the same address

My delicious discovery of Ida’s middle name did not seem important, but a search of 19th Century literature determined that this Medieval French name almost never occurs, but “Celanire” is the author of eleven short sketches between March and July of 1879, the first in Potter’s American Monthly and the rest in the Saturday Evening Post. This is the only writer using the name in the English language during the 19th century, and both journals’ offices were closer to the 21-year old Ida’s home than my home is to her grave. I am pleased to share this connection as a certainty.

Ida Celanire Craddock was born in Philadelphia on August 1, 1857 as the only surviving child of Elizabeth “Lizzie” S. Craddock (later Decker), who remained the dominant force throughout the life of her brilliant daughter. Ida’s father was Joseph T. Craddock, who was previously married and widowed in 1852 with four children between ages nine and seventeen.

Lizzie entered the Craddock family around March, 1855 and gave birth to the first Ida Craddock at the end of that year. This Ida lived just seven months and was buried beside Joseph’s first wife, with no middle initial on the record. Lizzie’s second daughter, Ida C. Craddock, arrived thirteen months after her sister’s death. The first Ida re-emerges in the story later because she seems to become “Nana,” the spirit sibling who was important in Craddock’s mystical life.

Ida’s father died when she, his youngest child, was six months old. Three years later and just prior to the Civil War, Ida lived with her mother, her 20-year old stepsister Rebecca Craddock, and one servant. Rebecca married in 1864, so we can presume that Ida had an adult stepsister in her daily life until she was seven years old. However, Rebecca Craddock’s existence has been missed till now, along with much else I now share with the reader regarding the early life of Ida Craddock.

It has been repeated that both Ida’s parents were Quakers, but it was at a time when that religion was at its lowest level of activity in hundreds of years. Neither Ida nor her mother was recorded as a Quaker, and except in the fact that Ida attended the Friends Central School between ages sixteen and nineteen, and also she was involved in other Quaker-based activities (not scarce in Philadelphia) as the years passed. In one letter Ida mentions her “French blood,” and indeed Lizzie gave France as both her parents’ birthplace in the 1880 census. If this was a Quaker family, the Religious Society of Friends did not record it as such.

Previous writers have given sketchy information on Lizzie Decker’s later marriages, again because they overlooked the Brown Family plot at Woodlands Cemetery, which was created in November 1870 when the second husband James M. Brown died, and “L. S. Brown” lived at 1032-1034 Race Street with her 12-year old daughter Ida and one servant.

James M. Brown (c.1821, Ireland) was a produce merchant, listed as a gentleman from 1865, who lived at 1034 Race Street starting in 1867. We find no record of a marriage, but in his will, James left his entire estate to his wife, Elizabeth S. Brown, who was listed as his widow in the city directory for at least four years after his death. Lizzie was now a slightly rich, independent businesswoman.

Samuel B. Selvage (b. 1808, NJ) was a 72-year old retired merchant and a widower, in 1880. The younger of his two sons was a little older than Ida Craddock. From 1874 he was listed as a clerk, living at the medicine store on Race. Nine years later (1883), Selvage died and was buried alongside Mr. Brown. This old man may have been Lizzie’s husband, or her father, or just a boarder who became her friend and who could afford a proper grave. He leads us to the question, Where did Lizzie S. Decker come from, and what was her maiden name? If it was Selvage, we simply can’t place her.

Thomas B. Decker looks to be Lizzie’s last husband. From 1878 through 1886 he lived at 1034 Race, and Lizzie, who has by now gone from Craddock to Brown to Craddock again, takes on Decker as her final surname in 1880. But these entries in the city directory are the only reasons why we connect Thomas and Lizzie Decker at all. In 1879 only, there was also a boarder named Charles L. Decker at the same address

Ida Celanire Craddock

Ida Celanire Craddock

Everyone interested in Ida Craddock, from her birth till our day, has seen her in Lizzie’s shadow, but none have observed the general path of Lizzie’s life, which is one of mystery. This is the woman who publicly shamed Ida for using Mrs. when not married to a living man, but we find no marriage document for any of Lizzie’s own three. We do not know her maiden name, nor do we have any sure evidence of Lizzie before the birth of the first Ida in 1855, at 23 years of age. In the space of three years, Lizzie inherits a profitable downtown patent medicines business and we understand that she teaches the young Ida about Spiritualism. At thirty-eight, she inherits another husband’s estate and raises Ida in comfort and privilege. The third (or possibly fourth) marriage to Mr. Decker only preserves Lizzie’s status as a married woman and grows the mystery she left to modern admirers of her remarkable daughter, Ida. Lizzie’s other activities during the 1890s included the Indian Rights Association and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, but she did not become prominent in either.

Lizzie S. Decker was a woman with a very strong personality who remained in control of her household and increased her fortune throughout her life, but who also sold snake oil for over forty years and who may have created a new identity for herself as an intelligent young woman. This was the mysterious Lizzie Decker who raised the wondrous Ida Craddock to possess such a powerful mind and fiercely independent spirit. Her best friend, Katie Stewart Wood, wrote after Ida’s death,

“My acquaintance with Miss Ida C. Craddock began when she was about sixteen years of age… In appearance, she was very beautiful –a fine, clear complection, with cameo-cut features and glorious, brilliant blue eyes. Her hands were remarkable for their delicate, tapering fingers. She stood and carried herself assertively, but had great charm of manner and was most fascinating in speech.

“Miss Craddock was unfortunate in her choice of friends and came under the influence of a woman and her husband who used her gifts.

“Born in affluent surroundings and cultivation, with every advantage of education and friends…

She “had knowledge of the French, German, Italian, Latin and Greek languages. With the history and literature of the world, her mental capacity and memory were astounding.”

“She was a victim of easy friends, and later, circumstances, and was finally sacrificed to the monsters of creation who kill what they cannot understand.”

Indeed the young Ida was in love with the world around her. A letter to Katie of July 1877 describes Ida’s journey from Philadelphia to Bristol, on her way to Freehold, NJ for a vacation:

“Our road lay between fine residences, and between fields of corn and ripened grain; tall trees shaded the greater part of the way, and the early sunlight slanted through their branches, falling in golden strips across our path. In sheltered corners the grass and flowers still bent under the moisture of the previous night, and all about us, from every plant, and from the Earth, there rose a delightful, dewey fragrance. Birds chirped and twittered on all sides, sometimes we heard a faraway rooster crow exultingly, or a horse neigh in some adjoining stable. Then, as the morning advanced, we met farmers trudging to their work, a plow-boy or two, whistling cheerily, and groups of children laughing on their way to school. Altogether, it was a most delightful drive.”

Later in the same letter, she mentioned that she was “studying, or attempting to study, phonography.”

Such was the bright young woman who penned the short pieces under the name Celanire in the following year, in which the first, “An Old Maid’s Reverie,” a middle-aged ‘Edna Ripley’ describes falling in love when she was young and, by way of a misplaced note, losing her young man to her own best friend. She learns of the mistake but keeps it secret so as not to cast a shadow over the new couple’s happiness. Instead of nursing a broken heart, Edna turned a def ear to all suitors and, “I was seized with a restless longing for some useful employment, in which I could forget my grief. For a while I had what Aunt Maria called ‘a missionary fit;’ I busied myself not only among the poor, but also among the people of our village, started a sewing school, a reading circle, and an art club. But, as I grew older, the quiet village life became wearisome, and I went to the city. There I wrote essays, pamphlets, and books, and by dint of hard labor, won a position that brought me in contact with learned and cultured men and women. Then, when I had grown into a busy life, the old, aching pain in my heart began to cease. I learned to take joy in life, just as it was.”

This passage could not better describe the spirit and the goals with which Ida entered the struggles of her adult life, and the first struggle began a few years later.

During the spring of 1882, Ida self-published a short textbook for learning phonetic shorthand. In the preface, she wrote: “This volume is the outgrowth of the author’s experience as a teacher of phonography at Girard College.” This means that in the space of five years, Ida went from no knowledge of shorthand to teaching it for pay and then to being a published expert in the field. In the back of the book are testimonials by authors and teachers of the subject, all strongly recommending Craddock’s new book as “clear and concise” and “the best book ever printed” for beginners. Although self-published, the little volume is impressive, with fine paper, extensive diagrams, and gilt page-edges.

In the Fall of 1882, the Faculty of the Arts at the University of Pennsylvania reported to the Board of Trustees that “Miss Ida C. Craddock passed the entrance examinations very satisfactorily, and that they respectfully refer to the board her application for admission to the Freshman Class.”

For the next meeting, a subcommittee of the Board then drew up a plan for the creation of a “women’s section” of the College of Arts. Ida was offered practical assistance in proceeding with her studies while the plan was being implemented. Then, the minutes state, “after a full discussion of the report it was, on motion of Bishop Stevens resolved that the Board of Trustees deem it inexpedient at this time to admit any women to the Department of Arts.”

At the same meeting, it was resolved “that the Trustees will organize a separate Collegiate Department for the complete education of women, so soon as funds are received sufficient to meet the expense thereof.”

Rt. Rev. William Bacon Stevens was Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania. Earlier in life, he had been a “professor of moral philosophy” and then the rector of a church in Philadelphia.

All that was in October and November of 1882. From December through the following autumn, Ida sent letters to the Board of Trustees, requesting a formal reply to her application for admission, and then announcing her intent to present herself “for examination with the Sophomore Class.” She was never to attend classes at the University of Pennsylvania.

According to one of the University’s web sites, “More than fifty years passed before the College for Women matriculated its first students.”

According to a letter to Katie from San Francisco (October 1, 1889), Ida has been on the West coast since the summer. Although she has connections over there, and she has been helped by friends, she has had a very hard time in making ends meet. Refusing “infamy or suicide,” –and refusing to borrow too much from friends –she did domestic work in between jobs as a stenographer. One secretarial job took her on an enjoyable trip to Alaska. At the time of the letter she is teaching typewriting and shorthand, just about getting by. She remarks,

“Now that I have stood down in the ranks of the miserable workers whom I once despised, as a race beneath me, I know how they feel when they have to daily face the prospect of starvation and misery; and, God helping, I mean to work for them one and all, as long as I live.”

Also in the letter she implores Katie not to divulge to Ida’s mother any details of the letter, because she would surely use the information to torment her. She’s been reading Edward Bellamy’s book Looking Backward, and is strongly recommending it to Katie as a solution to the world’s ills. Also, Ida envisioned her own Salon for local intelligentsia when she’s gotten established again. She’s become influenced by William T. Stead, the editor of Borderland. This was a publication devoted to the discussion of the border-realm between the ordinary, physical world and the world of spirits. Stead was also the editor of Review of Reviews.

She has been invited by Richard Westbrook to assist him in a “public matter” he’s planning back in Philly, (founding the American Secular Union), and so looks forward to returning there.

Richard Brodhead Westbrook was the son of a Pennsylvania politician. He became a lawyer, and also earned a Doctorate in Divinity. During his long life he went from being a Methodist minister to being a leading atheist scholar. By the time we find his name in Ida’s letters, Westbrook is 69 years old and has published several books, including three debunking the Bible, one on Girard College (which had defected from its secular charter) and others in favor of marriage, but critical of the church’s involvement in marriage and laws pertaining to it. His second wife, Henrietta Payne Westbrook, was a respected physician who Voltairine de Cleyre described as “Strong though quiet.” Henrietta sometimes lectured in the radical clubs on marriage and on public health issues. This couple is the same that was mentioned by Ida’s friend Katie, as the “unfortunate choice of friends” who used her gifts.

At the American Secular Union’s 14th Annual Congress at Portsmouth, Ohio (Oct. 31-Nov 2, 1890), Ida and the Westbrooks met two anarchists who would later share the radical club life with them in Philadelphia. These were the 24 year old Voltairine de Cleyre, a scheduled speaker, and George Brown (1858-1915), an English shoemaker who had spent five years training Indian workers at an army boot factory in Cawnpore, and then migrated to Chicago in time to witness the Haymarket police riot in May 1886.

Lizzie S. Decker was a woman with a very strong personality who remained in control of her household and increased her fortune throughout her life, but who also sold snake oil for over forty years and who may have created a new identity for herself as an intelligent young woman. This was the mysterious Lizzie Decker who raised the wondrous Ida Craddock to possess such a powerful mind and fiercely independent spirit. Her best friend, Katie Stewart Wood, wrote after Ida’s death,

“My acquaintance with Miss Ida C. Craddock began when she was about sixteen years of age… In appearance, she was very beautiful –a fine, clear complection, with cameo-cut features and glorious, brilliant blue eyes. Her hands were remarkable for their delicate, tapering fingers. She stood and carried herself assertively, but had great charm of manner and was most fascinating in speech.

“Miss Craddock was unfortunate in her choice of friends and came under the influence of a woman and her husband who used her gifts.

“Born in affluent surroundings and cultivation, with every advantage of education and friends…

She “had knowledge of the French, German, Italian, Latin and Greek languages. With the history and literature of the world, her mental capacity and memory were astounding.”

“She was a victim of easy friends, and later, circumstances, and was finally sacrificed to the monsters of creation who kill what they cannot understand.”

Indeed the young Ida was in love with the world around her. A letter to Katie of July 1877 describes Ida’s journey from Philadelphia to Bristol, on her way to Freehold, NJ for a vacation:

“Our road lay between fine residences, and between fields of corn and ripened grain; tall trees shaded the greater part of the way, and the early sunlight slanted through their branches, falling in golden strips across our path. In sheltered corners the grass and flowers still bent under the moisture of the previous night, and all about us, from every plant, and from the Earth, there rose a delightful, dewey fragrance. Birds chirped and twittered on all sides, sometimes we heard a faraway rooster crow exultingly, or a horse neigh in some adjoining stable. Then, as the morning advanced, we met farmers trudging to their work, a plow-boy or two, whistling cheerily, and groups of children laughing on their way to school. Altogether, it was a most delightful drive.”

Later in the same letter, she mentioned that she was “studying, or attempting to study, phonography.”

Such was the bright young woman who penned the short pieces under the name Celanire in the following year, in which the first, “An Old Maid’s Reverie,” a middle-aged ‘Edna Ripley’ describes falling in love when she was young and, by way of a misplaced note, losing her young man to her own best friend. She learns of the mistake but keeps it secret so as not to cast a shadow over the new couple’s happiness. Instead of nursing a broken heart, Edna turned a def ear to all suitors and, “I was seized with a restless longing for some useful employment, in which I could forget my grief. For a while I had what Aunt Maria called ‘a missionary fit;’ I busied myself not only among the poor, but also among the people of our village, started a sewing school, a reading circle, and an art club. But, as I grew older, the quiet village life became wearisome, and I went to the city. There I wrote essays, pamphlets, and books, and by dint of hard labor, won a position that brought me in contact with learned and cultured men and women. Then, when I had grown into a busy life, the old, aching pain in my heart began to cease. I learned to take joy in life, just as it was.”

This passage could not better describe the spirit and the goals with which Ida entered the struggles of her adult life, and the first struggle began a few years later.

During the spring of 1882, Ida self-published a short textbook for learning phonetic shorthand. In the preface, she wrote: “This volume is the outgrowth of the author’s experience as a teacher of phonography at Girard College.” This means that in the space of five years, Ida went from no knowledge of shorthand to teaching it for pay and then to being a published expert in the field. In the back of the book are testimonials by authors and teachers of the subject, all strongly recommending Craddock’s new book as “clear and concise” and “the best book ever printed” for beginners. Although self-published, the little volume is impressive, with fine paper, extensive diagrams, and gilt page-edges.

In the Fall of 1882, the Faculty of the Arts at the University of Pennsylvania reported to the Board of Trustees that “Miss Ida C. Craddock passed the entrance examinations very satisfactorily, and that they respectfully refer to the board her application for admission to the Freshman Class.”

For the next meeting, a subcommittee of the Board then drew up a plan for the creation of a “women’s section” of the College of Arts. Ida was offered practical assistance in proceeding with her studies while the plan was being implemented. Then, the minutes state, “after a full discussion of the report it was, on motion of Bishop Stevens resolved that the Board of Trustees deem it inexpedient at this time to admit any women to the Department of Arts.”

At the same meeting, it was resolved “that the Trustees will organize a separate Collegiate Department for the complete education of women, so soon as funds are received sufficient to meet the expense thereof.”

Rt. Rev. William Bacon Stevens was Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania. Earlier in life, he had been a “professor of moral philosophy” and then the rector of a church in Philadelphia.

All that was in October and November of 1882. From December through the following autumn, Ida sent letters to the Board of Trustees, requesting a formal reply to her application for admission, and then announcing her intent to present herself “for examination with the Sophomore Class.” She was never to attend classes at the University of Pennsylvania.

According to one of the University’s web sites, “More than fifty years passed before the College for Women matriculated its first students.”

According to a letter to Katie from San Francisco (October 1, 1889), Ida has been on the West coast since the summer. Although she has connections over there, and she has been helped by friends, she has had a very hard time in making ends meet. Refusing “infamy or suicide,” –and refusing to borrow too much from friends –she did domestic work in between jobs as a stenographer. One secretarial job took her on an enjoyable trip to Alaska. At the time of the letter she is teaching typewriting and shorthand, just about getting by. She remarks,

“Now that I have stood down in the ranks of the miserable workers whom I once despised, as a race beneath me, I know how they feel when they have to daily face the prospect of starvation and misery; and, God helping, I mean to work for them one and all, as long as I live.”

Also in the letter she implores Katie not to divulge to Ida’s mother any details of the letter, because she would surely use the information to torment her. She’s been reading Edward Bellamy’s book Looking Backward, and is strongly recommending it to Katie as a solution to the world’s ills. Also, Ida envisioned her own Salon for local intelligentsia when she’s gotten established again. She’s become influenced by William T. Stead, the editor of Borderland. This was a publication devoted to the discussion of the border-realm between the ordinary, physical world and the world of spirits. Stead was also the editor of Review of Reviews.

She has been invited by Richard Westbrook to assist him in a “public matter” he’s planning back in Philly, (founding the American Secular Union), and so looks forward to returning there.

Richard Brodhead Westbrook was the son of a Pennsylvania politician. He became a lawyer, and also earned a Doctorate in Divinity. During his long life he went from being a Methodist minister to being a leading atheist scholar. By the time we find his name in Ida’s letters, Westbrook is 69 years old and has published several books, including three debunking the Bible, one on Girard College (which had defected from its secular charter) and others in favor of marriage, but critical of the church’s involvement in marriage and laws pertaining to it. His second wife, Henrietta Payne Westbrook, was a respected physician who Voltairine de Cleyre described as “Strong though quiet.” Henrietta sometimes lectured in the radical clubs on marriage and on public health issues. This couple is the same that was mentioned by Ida’s friend Katie, as the “unfortunate choice of friends” who used her gifts.

At the American Secular Union’s 14th Annual Congress at Portsmouth, Ohio (Oct. 31-Nov 2, 1890), Ida and the Westbrooks met two anarchists who would later share the radical club life with them in Philadelphia. These were the 24 year old Voltairine de Cleyre, a scheduled speaker, and George Brown (1858-1915), an English shoemaker who had spent five years training Indian workers at an army boot factory in Cawnpore, and then migrated to Chicago in time to witness the Haymarket police riot in May 1886.

Voltairine de Cleyre in 1890

Voltairine de Cleyre in 1890

Voltairine de Cleyre (1866-1912) was then a newcomer to the anarchist movement and just starting on the most intense and productive period of her life. A year earlier, had moved from Grand Rapids, MI to Philadelphia where she bore her son Harry, conceived by accident, in June 1890. After a difficult childbirth, Voltairine left her baby with the father, Painite lecturer James B. Elliott, and spent almost a year in Enterprise KS as a speaker for the Woman’s National Liberal Union. An excursion from Kansas now found her at the event in Ohio.

Brown and de Cleyre were meeting for the first time. Their acquaintance became a friendship which lasted over twenty years and had a major effect on the lives of both. As George later recalled, Voltairine recited a poem “that would have been considered incendiary in any other than poetic form,” and she closed the conference with a speech on the moral standards of atheist men and women that was “mainly metaphysical,” and impressed her listeners greatly.

For about three years (1889-92), Ida served as corresponding secretary of the American Secular Union, handling the group’s mail, helping to produce the Truth Seeker, hiring its paid speakers, arranging its conventions, and judging an essay contest alongside the eminent ethnologist Daniel G. Brinton, who was anarchist for his last ten years of life. It was Ida who had engaged de Cleyre to speak in Portsmouth.

Brown and de Cleyre were meeting for the first time. Their acquaintance became a friendship which lasted over twenty years and had a major effect on the lives of both. As George later recalled, Voltairine recited a poem “that would have been considered incendiary in any other than poetic form,” and she closed the conference with a speech on the moral standards of atheist men and women that was “mainly metaphysical,” and impressed her listeners greatly.

For about three years (1889-92), Ida served as corresponding secretary of the American Secular Union, handling the group’s mail, helping to produce the Truth Seeker, hiring its paid speakers, arranging its conventions, and judging an essay contest alongside the eminent ethnologist Daniel G. Brinton, who was anarchist for his last ten years of life. It was Ida who had engaged de Cleyre to speak in Portsmouth.

George Brown in 1911

George Brown in 1911

Responding to local news reports in August 1893 of a young Danish woman’s rape on Woodland Avenue, at the edge of the cemetery and very near to where her own grave would later be, Craddock wrote to the Public Ledger recommending the castration of rapists upon their release from prison. Public outrage was stoked because the victim spoke no English and was stranded in the dark night after taking the wrong trolley.

“So long as capital punishment is recognized as a legitimate means of protection of the community from the murderer,” Ida wrote, “just so long ought castration be recognized as an equally legitimate means of protecting our women from the future criminal assaults of such men.”

The two condemned rapists received 15 year sentences.

On a Tuesday evening in early 1894, Ida addressed the Ladies Liberal League of Philadelphia at its weekly meeting at Ridge Avenue & Green Street. The L.L.L. had been created two years earlier because the much older Friendship Liberal League, with its “tendency to smoothness and respectability” had been refusing to host lectures on Free Love, anarchism, and controversial women subjects. The new club welcomed male members, but only women could serve as its officers and most of its leading members were anarchists.

The Westbrooks were both in attendance. Richard Westbrook had lobbied to have Ida’s name struck from the speakers’ list, but de Cleyre had insisted she be heard. The evening’s topic was “Celestial Bridegrooms.” Ida believed that she was married to a spirit, and that she and the spirit-husband had sex on a regular basis. Voltairine later remarked that the “scholarly” Miss Craddock had “been denied a platform by every thin-shelled liberal society in the city, because she thinks that can happen now which every ex-Christian freethinker once devoutly believed did happen 1900 years ago! Observe how little they are really changed, since they are now as ready to persecute belief as once they were to persecute unbelief.”

Indeed Ida gave dozens of examples of scripture and passages from the early “church fathers” to support what she had written in her pamphlet Heavenly Bridegrooms: “It has been my high privilege to have some practical experience as the earthly wife of an angel from the unseen world. In the interests of psychical research, I have tried to explore this pathway of communication with the spiritual universe, and so far as lay in my power, to make a rough guidebook of the route.”

Ida wrote that summer to James B. Elliott & de Cleyre from London, where she has fled form an attempt by her mother to have her committed to an asylum. At that time, mental institutions were easy for unusual, spirited women to be committed to, and were often impossible to escape. Dr Henrietta Westbrook had given Ida shelter and helped her make the escape.

She had been in London at least four months under the name “Mrs. Irene S. Roberts.” — presenting herself as a married woman. She asked Elliott and de Cleyre,

“By the way, would you mind telling me if you remember hearing a pistol click on the night that I delivered said discourse? Everybody was sitting as still as death, and I was beginning to speak of the Catholic Church, when I heard something that sounded wonderfully like the cocking of a pistol. It flashed into my mind that perhaps the Catholic Church had sent an emissary there who was prepared to silence me.”

Ida assured them that this was not a “spirit sound,” but a “veritably physical, objective sound.”

By the time of that lecture, Ida Craddock was already being watched by Anthony Comstock, the brutal agent of the US Post Office, for having mailed an allegedly “obscene” tract on Belly Dancing. Soon she was stalked and hounded by her mother as well for being insane.

By the standards of most people (especially today), Ida was fairly delusional, but never in such a way that prevented her from earning her living; never a danger to anyone. She was a spiritualist, as were a great many very fine minds of her century. Her true offense to Victorian society was that her beliefs were non-Christian, and Ida was a woman intellectual. Ida developed her Spiritualist ideas in a special, working class direction when, in Heaven of the Bible (1897), she wrote,

“I venture to set down a few of the industries and industrial workers which the Bible glimpses of life in Heaven suggest will be or have been at some time necessary: Stone-cutters and polishers… Harp-makers. Trumpet-makers… Gardeners to attend the plants in Paradise… Weapons for Michael and his angels and for ‘the armies of Heaven’ generally… Charioteer… Tooth-brushes to be used after each luncheon from the tree of life.”

Ida had not forgotten how it felt when she had “stood down in the ranks of the miserable workers whom I once despised.” She seems about to organize trade unions in the clouds.

As the century drew near to its end, Voltairine and Ida socialized in different circles, but probably read several of the same periodicals. In addition, both women were friends of Moses Harman and his daughter Lillian, the leading free-love, individualist anarchists and publishers of the newspaper Lucifer The Light-Bearer. Both these firebrands were entering the ugliest years of their lives as well. Ida would be jailed and confined to an asylum, then end her own life to spare herself more abuse and senseless violence. Between 1897 and 1905, Voltairine would have a very risky abortion, she would be shot and nearly killed by a mentally ill former pupil and comrade, and then the frail anarchist would have a near brush with death by syphilis, that then-unmentionable and incurable scourge.

De Cleyre was 30 years old when, during the late summer or fall of 1897, she wrote her lover a letter in London. The letter was never finished, nor was it signed, dated, or mailed. Yet the letter, clearly in her handwriting and style, now rests among the papers of Joseph J. Cohen, de Cleyre’s longtime associate in anarchism, which are stored in the YIVO Archives in New York City. It is one of the most compelling and dramatic of all her known writings.

Samuel H. Gordon (1871-1906) was a Russian Jew who had arrived in Philadelphia by 1890, found work as a cigar roller, and later attended the Medico-Chirurgical College, graduating as an MD in 1898. Gordon followed the anarchist-communism of Johann Most and was active during his six years of romance with Voltairine, but he was no deep thinker and was detested my many who knew him. In the letter she responds to his lurid accusations of infidelity with a supposedly drunken man, and she reminds him of the dangerous procedure she’s had to endure while continuing her public lectures. Part of the letter reads:

“If you had a grain of common sense in the matter, you would remember that I had just been to Dr. Sittkamp and know that (as a medical student) no woman is supposed to be making journeys at such times, much less coming into contact with men; if you had to go through the horrible nausea, faintness, loss of ability to think, and the danger of the whole thing happening on the train or the boat; if you had lain on the Fall River steamer (by the way you had better go to the steamer books and inquire about that) as I did with a corset stay inside of that organ which you delight in theorizing about; if you had stood as I did with Harry Kelly on the street-corner, Sunday morning, April 26, and realized that the longed-for result was about to happen, there on the street, –if you had gone through the fear of that, and been compelled to sit talking to people afterwards and wondering how you were going to get to the closet in time; if you had had this happen at one o’clock and been compelled to lecture at 3; if this had been your sequel of a pleasurable experience with me, as it was mine with you, you would be ashamed to talk to me of McLuckie in such a way.”

The letter illustrates not only the harrowing experience of the abortion, but it also shows how utterly devoted Voltairine was to her cause. She could have stayed in bed with friends on hand, but she was compelled to spread the idea, with her last breath if need be.

A different (and equally important) part of this letter was quoted by the great historian Paul Avrich in his definitive 1978 biography An American Anarchist: The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre (p. 84), but he did not quote or refer to the part of the letter which describes her abortion. Apparently Avrich was the first, and I was the second and last researcher to read this letter, since no other writer has made reference to it anywhere, except to repeat Avrich’s quotation. We do not know whether Paul simply missed the slightly veiled language describing the abortion or consciously omitted to mention it, but either scenario is possible. He was directly in touch with de Cleyre’s descendants, some of whom were sensitive about the family’s internal history. I asked Paul about it, but the illness that killed him robbed us of his answer as well. He could not remember.

In March 1902, now in New York City, when the authorities seized her pamphlet of marriage advice called The Wedding Night, Ida was convicted and sentenced to another 3 months on Blackwell’s Island. The purpose of this “obscene” text was to provide simple information on sex to newlyweds. There existed a widespread problem in those days, where a bride would not understand that she’d be expected to have intercourse with her new husband, on the night following the wedding. Also, men would go into marriage not knowing that the woman would be traumatized by sex that they didn’t want, and so rape their wives after the wedding.

While incarcerated, it was reported that Ida was “brutally and forcibly vaccinated in the prison, as she objected to it and resisted.” Upon her released she was charged under a federal statute for the selfsame mailings. By October she had been convicted and faced a sure five years in prison. This was not an acceptable option for Ida’s civilized heart and mind, so she chose suicide. On the 16th she did not go to court, but instead wrote two letters –one to Lizzie, the other to the public.

To Lizzie, Ida wrote (in part), “The real Ida, your own daughter, loves you and waits for you to soon come over to join her in the beautiful, blessed world beyond the grave, where depraved Comstocks and corrupt judges and impure-minded people are not known…

“Please be sure, mother, not to let my body be buried until it has begun to gangrene. You know you promised me this long ago. I have a great horror of being put into a coffin alive. Don’t trust the say-so of any physician.”

In her long public letter, Ida spoke of Anthony Comstock, the man who crafted her destruction:

“The man is a sex pervert; he is what physicians term a Sadist –namely a person in whom the impulses of cruelty arise concurrently with the stirring of sex emotion.”

Ida stayed in her room, opened a gas jet, opened the veins of her arm and died –perhaps to join her husband Soph on the other side of her universe. Her funeral and burial were kept private and Ida’s notes were published. A month after Ida was gone, her mother wrote praising words of her daughter without acknowledging her own errors, or even showing that she had understood a single word spoken by her daughter in 45 years.

The timeless words from Lizzie were, “That woman was as pure as God’s snow and as chaste as His ice.” Lizzie S. Decker died two years later and was buried alongside Ida. No one has been buried in the family plot after Lizzie.

On 19 December 1902, two months after Ida Craddock killed herself, Herman Helcher shot Voltairine de Cleyre three times as she waited for a trolley car, very nearly killing her. This was a critical event in the story of anarchism in Philadelphia. Herman was a former language student of hers and an anarchist who had lost his sanity from a fever around 1895. All that was known of Herman’s origins until 2013 was that he was a Jewish immigrant from Russia, but then I was contacted by a living relative and now we have a fair picture of his whole life. Herman was actually Chaim Helcher, born at Daugavpils, Latvia and had come to the US with his mother and sister around 1888.

By 1902, Voltairine was already fairly well-known in the international movement for her many essays and poems that had been published in anarchist and other radical periodicals. Locally, she was one of the two best-known anarchist speakers of English, along with George Brown.

Herman stood waiting, wearing a false moustache and eyeglasses. When he was arrested, he told the police, “I don’t want to live. We were sweethearts. She broke my heart and deserved to be killed.” De Cleyre was helped by strangers, particularly the 17-year old African-American Alice Gorgas, who later became an actor. Gorgas invited Voltairine to come inside her home (407 Green) while help was summoned. Soon she was taken by a horse-drawn police wagon to Hahnemann, a Homeopathic hospital. The doctors quickly declared the bleeding anarchist lady doomed, but then her friends began to arrive. George was first, and he insisted that no expense be spared in saving Voltairine, because she was very special.

“So long as capital punishment is recognized as a legitimate means of protection of the community from the murderer,” Ida wrote, “just so long ought castration be recognized as an equally legitimate means of protecting our women from the future criminal assaults of such men.”

The two condemned rapists received 15 year sentences.

On a Tuesday evening in early 1894, Ida addressed the Ladies Liberal League of Philadelphia at its weekly meeting at Ridge Avenue & Green Street. The L.L.L. had been created two years earlier because the much older Friendship Liberal League, with its “tendency to smoothness and respectability” had been refusing to host lectures on Free Love, anarchism, and controversial women subjects. The new club welcomed male members, but only women could serve as its officers and most of its leading members were anarchists.

The Westbrooks were both in attendance. Richard Westbrook had lobbied to have Ida’s name struck from the speakers’ list, but de Cleyre had insisted she be heard. The evening’s topic was “Celestial Bridegrooms.” Ida believed that she was married to a spirit, and that she and the spirit-husband had sex on a regular basis. Voltairine later remarked that the “scholarly” Miss Craddock had “been denied a platform by every thin-shelled liberal society in the city, because she thinks that can happen now which every ex-Christian freethinker once devoutly believed did happen 1900 years ago! Observe how little they are really changed, since they are now as ready to persecute belief as once they were to persecute unbelief.”

Indeed Ida gave dozens of examples of scripture and passages from the early “church fathers” to support what she had written in her pamphlet Heavenly Bridegrooms: “It has been my high privilege to have some practical experience as the earthly wife of an angel from the unseen world. In the interests of psychical research, I have tried to explore this pathway of communication with the spiritual universe, and so far as lay in my power, to make a rough guidebook of the route.”

Ida wrote that summer to James B. Elliott & de Cleyre from London, where she has fled form an attempt by her mother to have her committed to an asylum. At that time, mental institutions were easy for unusual, spirited women to be committed to, and were often impossible to escape. Dr Henrietta Westbrook had given Ida shelter and helped her make the escape.

She had been in London at least four months under the name “Mrs. Irene S. Roberts.” — presenting herself as a married woman. She asked Elliott and de Cleyre,

“By the way, would you mind telling me if you remember hearing a pistol click on the night that I delivered said discourse? Everybody was sitting as still as death, and I was beginning to speak of the Catholic Church, when I heard something that sounded wonderfully like the cocking of a pistol. It flashed into my mind that perhaps the Catholic Church had sent an emissary there who was prepared to silence me.”

Ida assured them that this was not a “spirit sound,” but a “veritably physical, objective sound.”

By the time of that lecture, Ida Craddock was already being watched by Anthony Comstock, the brutal agent of the US Post Office, for having mailed an allegedly “obscene” tract on Belly Dancing. Soon she was stalked and hounded by her mother as well for being insane.

By the standards of most people (especially today), Ida was fairly delusional, but never in such a way that prevented her from earning her living; never a danger to anyone. She was a spiritualist, as were a great many very fine minds of her century. Her true offense to Victorian society was that her beliefs were non-Christian, and Ida was a woman intellectual. Ida developed her Spiritualist ideas in a special, working class direction when, in Heaven of the Bible (1897), she wrote,

“I venture to set down a few of the industries and industrial workers which the Bible glimpses of life in Heaven suggest will be or have been at some time necessary: Stone-cutters and polishers… Harp-makers. Trumpet-makers… Gardeners to attend the plants in Paradise… Weapons for Michael and his angels and for ‘the armies of Heaven’ generally… Charioteer… Tooth-brushes to be used after each luncheon from the tree of life.”

Ida had not forgotten how it felt when she had “stood down in the ranks of the miserable workers whom I once despised.” She seems about to organize trade unions in the clouds.

As the century drew near to its end, Voltairine and Ida socialized in different circles, but probably read several of the same periodicals. In addition, both women were friends of Moses Harman and his daughter Lillian, the leading free-love, individualist anarchists and publishers of the newspaper Lucifer The Light-Bearer. Both these firebrands were entering the ugliest years of their lives as well. Ida would be jailed and confined to an asylum, then end her own life to spare herself more abuse and senseless violence. Between 1897 and 1905, Voltairine would have a very risky abortion, she would be shot and nearly killed by a mentally ill former pupil and comrade, and then the frail anarchist would have a near brush with death by syphilis, that then-unmentionable and incurable scourge.

De Cleyre was 30 years old when, during the late summer or fall of 1897, she wrote her lover a letter in London. The letter was never finished, nor was it signed, dated, or mailed. Yet the letter, clearly in her handwriting and style, now rests among the papers of Joseph J. Cohen, de Cleyre’s longtime associate in anarchism, which are stored in the YIVO Archives in New York City. It is one of the most compelling and dramatic of all her known writings.

Samuel H. Gordon (1871-1906) was a Russian Jew who had arrived in Philadelphia by 1890, found work as a cigar roller, and later attended the Medico-Chirurgical College, graduating as an MD in 1898. Gordon followed the anarchist-communism of Johann Most and was active during his six years of romance with Voltairine, but he was no deep thinker and was detested my many who knew him. In the letter she responds to his lurid accusations of infidelity with a supposedly drunken man, and she reminds him of the dangerous procedure she’s had to endure while continuing her public lectures. Part of the letter reads:

“If you had a grain of common sense in the matter, you would remember that I had just been to Dr. Sittkamp and know that (as a medical student) no woman is supposed to be making journeys at such times, much less coming into contact with men; if you had to go through the horrible nausea, faintness, loss of ability to think, and the danger of the whole thing happening on the train or the boat; if you had lain on the Fall River steamer (by the way you had better go to the steamer books and inquire about that) as I did with a corset stay inside of that organ which you delight in theorizing about; if you had stood as I did with Harry Kelly on the street-corner, Sunday morning, April 26, and realized that the longed-for result was about to happen, there on the street, –if you had gone through the fear of that, and been compelled to sit talking to people afterwards and wondering how you were going to get to the closet in time; if you had had this happen at one o’clock and been compelled to lecture at 3; if this had been your sequel of a pleasurable experience with me, as it was mine with you, you would be ashamed to talk to me of McLuckie in such a way.”

The letter illustrates not only the harrowing experience of the abortion, but it also shows how utterly devoted Voltairine was to her cause. She could have stayed in bed with friends on hand, but she was compelled to spread the idea, with her last breath if need be.

A different (and equally important) part of this letter was quoted by the great historian Paul Avrich in his definitive 1978 biography An American Anarchist: The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre (p. 84), but he did not quote or refer to the part of the letter which describes her abortion. Apparently Avrich was the first, and I was the second and last researcher to read this letter, since no other writer has made reference to it anywhere, except to repeat Avrich’s quotation. We do not know whether Paul simply missed the slightly veiled language describing the abortion or consciously omitted to mention it, but either scenario is possible. He was directly in touch with de Cleyre’s descendants, some of whom were sensitive about the family’s internal history. I asked Paul about it, but the illness that killed him robbed us of his answer as well. He could not remember.

In March 1902, now in New York City, when the authorities seized her pamphlet of marriage advice called The Wedding Night, Ida was convicted and sentenced to another 3 months on Blackwell’s Island. The purpose of this “obscene” text was to provide simple information on sex to newlyweds. There existed a widespread problem in those days, where a bride would not understand that she’d be expected to have intercourse with her new husband, on the night following the wedding. Also, men would go into marriage not knowing that the woman would be traumatized by sex that they didn’t want, and so rape their wives after the wedding.

While incarcerated, it was reported that Ida was “brutally and forcibly vaccinated in the prison, as she objected to it and resisted.” Upon her released she was charged under a federal statute for the selfsame mailings. By October she had been convicted and faced a sure five years in prison. This was not an acceptable option for Ida’s civilized heart and mind, so she chose suicide. On the 16th she did not go to court, but instead wrote two letters –one to Lizzie, the other to the public.

To Lizzie, Ida wrote (in part), “The real Ida, your own daughter, loves you and waits for you to soon come over to join her in the beautiful, blessed world beyond the grave, where depraved Comstocks and corrupt judges and impure-minded people are not known…

“Please be sure, mother, not to let my body be buried until it has begun to gangrene. You know you promised me this long ago. I have a great horror of being put into a coffin alive. Don’t trust the say-so of any physician.”

In her long public letter, Ida spoke of Anthony Comstock, the man who crafted her destruction:

“The man is a sex pervert; he is what physicians term a Sadist –namely a person in whom the impulses of cruelty arise concurrently with the stirring of sex emotion.”

Ida stayed in her room, opened a gas jet, opened the veins of her arm and died –perhaps to join her husband Soph on the other side of her universe. Her funeral and burial were kept private and Ida’s notes were published. A month after Ida was gone, her mother wrote praising words of her daughter without acknowledging her own errors, or even showing that she had understood a single word spoken by her daughter in 45 years.

The timeless words from Lizzie were, “That woman was as pure as God’s snow and as chaste as His ice.” Lizzie S. Decker died two years later and was buried alongside Ida. No one has been buried in the family plot after Lizzie.

On 19 December 1902, two months after Ida Craddock killed herself, Herman Helcher shot Voltairine de Cleyre three times as she waited for a trolley car, very nearly killing her. This was a critical event in the story of anarchism in Philadelphia. Herman was a former language student of hers and an anarchist who had lost his sanity from a fever around 1895. All that was known of Herman’s origins until 2013 was that he was a Jewish immigrant from Russia, but then I was contacted by a living relative and now we have a fair picture of his whole life. Herman was actually Chaim Helcher, born at Daugavpils, Latvia and had come to the US with his mother and sister around 1888.

By 1902, Voltairine was already fairly well-known in the international movement for her many essays and poems that had been published in anarchist and other radical periodicals. Locally, she was one of the two best-known anarchist speakers of English, along with George Brown.

Herman stood waiting, wearing a false moustache and eyeglasses. When he was arrested, he told the police, “I don’t want to live. We were sweethearts. She broke my heart and deserved to be killed.” De Cleyre was helped by strangers, particularly the 17-year old African-American Alice Gorgas, who later became an actor. Gorgas invited Voltairine to come inside her home (407 Green) while help was summoned. Soon she was taken by a horse-drawn police wagon to Hahnemann, a Homeopathic hospital. The doctors quickly declared the bleeding anarchist lady doomed, but then her friends began to arrive. George was first, and he insisted that no expense be spared in saving Voltairine, because she was very special.

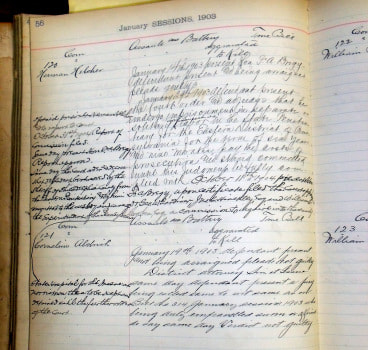

Court Record for Herman Helcher at City Archive

Court Record for Herman Helcher at City Archive

News of the shooting traveled very fast, and this is where the world of anarchist doctors steps into the light. The following day, the North American reported that Dr. William Williams Keen stopped in to look de Cleyre over and offer an opinion. Keen was one of the top surgeons on Earth and he was in no way associated with Hahnemann Hospital, the patient was poor, and the nation had not forgotten that its president had been assassinated by an anarchist only one year earlier. This famous surgeon’s presence and free advice would seem downright bizarre.

It turns out that Doctors Leo N. Gartman and Bernhard Segal, anarchist comrades of Voltairine’s, had been a students of Keen’s just eight years earlier at Thomas Jefferson Hospital, and both were now respected physicians. Her connections behind the scenes brought the “fair anarchist poet” back from death’s door.

Herman Helcher was brought in by police to be identified by his victim, but de Cleyre flatly refused to finger him, insisting that he needed care, not punishment. Helcher was quite mad, and we find a dozen different reports on his delusions of love and obsessions with various women.

Money was raised for Voltairine’s recovery and also for Herman’s legal defense. This rare level of forgiveness and charity in the week before Christmas won sympathy for de Cleyre throughout the country, but Herman was sentenced to six years of prison and spent the remaining decade of his life between mental hospitals, jails, and the care of his very loyal and caring family. Voltairine carried all three bullets in her body for the rest of her life because her homeopathic doctors chose to leave them there.

Voltairine de Cleyre had yet another close call with death, this time by syphilis, during the winter of 1904-1905. In those times, the word syphilis was never used outside of medical literature and if it were publicly connected to an individual, it would constitute a social death. Voltairine was a varietist, or serial monogamist, and sexually active since her early twenties. She was not especially promiscuous as far as we know, but more than enough to be regarded as “a public whore” by “some of the good women” of Arden, Delaware’s single-tax and socialist circles.

In the years after her death it was understood among de Cleyre’s friends that she suffered from the disease, but it remained only a strong rumor until recently, when I found proof. Since childhood she suffered from painful sinus infections and “catarrh of the nose” that had by 1904 created a terribly pounding in her ears and caused the roof of her mouth to atrophy. It was so bad that she spent July in hospital, then two months in the country, away from all the city’s noise and pollution. Finding no relief, Voltairine returned in October for a stay in Medico-Chirurgical Hospital at 17th & Cherry Streets. Her condition worsened to the point where Lucifer posted a premature obituary on the 27th and her friends again formed a committee to raise funds for her treatment and support. Sometimes she suffered deafness.

Voltairine, however, was not one to give up the struggle just because she was in continuous pain and could hardly speak or write. On Christmas Day of 1904, the Russian revolutionary exile Catherine Breshkovskaya made her second of six public fund-raising events in Philadelphia, at a theater seventeen blocks from her sick bed during a heavy blizzard. Because the insurrection against the Tzar was the most exciting news to develop during her lifetime, Voltairine walked through the snow and was able to exchange greetings with the old fighter. Some of her comrades who were born in the Russian Empire were hosting the Babushka (little granny) in their “co-operative” house (a radical thing then, shared by unmarried couples) and Natasha Notkin, a Lithuanian-born nihilist and free lover, had started the city’s Friends of Russian Freedom group. The Babushka’s events drew wild, overflowing crowds, and last year I learned that the Tzar’s Okhrana dispatched an agent named Movsa Tumarinson to live briefly at 507 Pine Street (close to many Jewish anarchists) that winter, posing as a dentist and leaving a woman pregnant before he vanished.

Voltairine left the hospital in January1905, but she had not yet recovered to robust health. On March 5th, Breshkovskaya made her fourth appearance in Philadelphia, with Alice Stone Blackwell presiding and featuring speakers in several languages. The English address was given by Rev. Russell H. Conwell, the city’s leading Baptist and founder of Temple University. Conwell gave the US constitution as the model for reform in Russia and stated that Breshkovskaya “has found here a land where, with her ideals of freedom, she will be perfectly at home.”

At that point Voltairine de Cleyre, although not scheduled to speak, asked to do so and was granted the podium. The next day’s Press stated that “she was pale and ill, but her voice rang like a tocsin and her utterances aroused great enthusiasm.”

Not as an American,” Voltairine began, “–though I am one –but as an anarchist, I welcome this noble woman to our ranks. I could not sit still and be silent hearing the truth told in every language but English. The international character of this meeting is a sign that people of all countries are against tyranny, whether in Italy, Russia, or America. But if I could not wish the Russian revolutionaries a better freedom than that which we have in America, I would say to them, ‘You had better lay down your arms.’ […]

It turns out that Doctors Leo N. Gartman and Bernhard Segal, anarchist comrades of Voltairine’s, had been a students of Keen’s just eight years earlier at Thomas Jefferson Hospital, and both were now respected physicians. Her connections behind the scenes brought the “fair anarchist poet” back from death’s door.

Herman Helcher was brought in by police to be identified by his victim, but de Cleyre flatly refused to finger him, insisting that he needed care, not punishment. Helcher was quite mad, and we find a dozen different reports on his delusions of love and obsessions with various women.

Money was raised for Voltairine’s recovery and also for Herman’s legal defense. This rare level of forgiveness and charity in the week before Christmas won sympathy for de Cleyre throughout the country, but Herman was sentenced to six years of prison and spent the remaining decade of his life between mental hospitals, jails, and the care of his very loyal and caring family. Voltairine carried all three bullets in her body for the rest of her life because her homeopathic doctors chose to leave them there.

Voltairine de Cleyre had yet another close call with death, this time by syphilis, during the winter of 1904-1905. In those times, the word syphilis was never used outside of medical literature and if it were publicly connected to an individual, it would constitute a social death. Voltairine was a varietist, or serial monogamist, and sexually active since her early twenties. She was not especially promiscuous as far as we know, but more than enough to be regarded as “a public whore” by “some of the good women” of Arden, Delaware’s single-tax and socialist circles.

In the years after her death it was understood among de Cleyre’s friends that she suffered from the disease, but it remained only a strong rumor until recently, when I found proof. Since childhood she suffered from painful sinus infections and “catarrh of the nose” that had by 1904 created a terribly pounding in her ears and caused the roof of her mouth to atrophy. It was so bad that she spent July in hospital, then two months in the country, away from all the city’s noise and pollution. Finding no relief, Voltairine returned in October for a stay in Medico-Chirurgical Hospital at 17th & Cherry Streets. Her condition worsened to the point where Lucifer posted a premature obituary on the 27th and her friends again formed a committee to raise funds for her treatment and support. Sometimes she suffered deafness.

Voltairine, however, was not one to give up the struggle just because she was in continuous pain and could hardly speak or write. On Christmas Day of 1904, the Russian revolutionary exile Catherine Breshkovskaya made her second of six public fund-raising events in Philadelphia, at a theater seventeen blocks from her sick bed during a heavy blizzard. Because the insurrection against the Tzar was the most exciting news to develop during her lifetime, Voltairine walked through the snow and was able to exchange greetings with the old fighter. Some of her comrades who were born in the Russian Empire were hosting the Babushka (little granny) in their “co-operative” house (a radical thing then, shared by unmarried couples) and Natasha Notkin, a Lithuanian-born nihilist and free lover, had started the city’s Friends of Russian Freedom group. The Babushka’s events drew wild, overflowing crowds, and last year I learned that the Tzar’s Okhrana dispatched an agent named Movsa Tumarinson to live briefly at 507 Pine Street (close to many Jewish anarchists) that winter, posing as a dentist and leaving a woman pregnant before he vanished.

Voltairine left the hospital in January1905, but she had not yet recovered to robust health. On March 5th, Breshkovskaya made her fourth appearance in Philadelphia, with Alice Stone Blackwell presiding and featuring speakers in several languages. The English address was given by Rev. Russell H. Conwell, the city’s leading Baptist and founder of Temple University. Conwell gave the US constitution as the model for reform in Russia and stated that Breshkovskaya “has found here a land where, with her ideals of freedom, she will be perfectly at home.”

At that point Voltairine de Cleyre, although not scheduled to speak, asked to do so and was granted the podium. The next day’s Press stated that “she was pale and ill, but her voice rang like a tocsin and her utterances aroused great enthusiasm.”

Not as an American,” Voltairine began, “–though I am one –but as an anarchist, I welcome this noble woman to our ranks. I could not sit still and be silent hearing the truth told in every language but English. The international character of this meeting is a sign that people of all countries are against tyranny, whether in Italy, Russia, or America. But if I could not wish the Russian revolutionaries a better freedom than that which we have in America, I would say to them, ‘You had better lay down your arms.’ […]

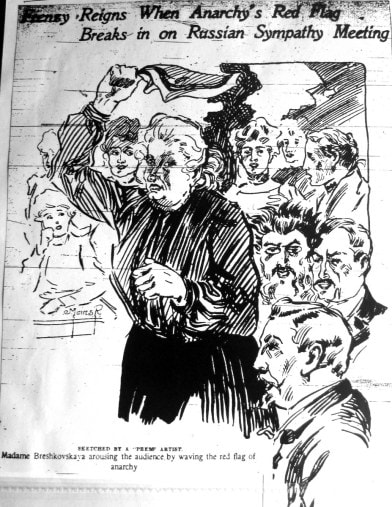

The Babushka at Philadelphia, depicted in the Press. A sickly Voltairine appears at upper right (1905).

The Babushka at Philadelphia, depicted in the Press. A sickly Voltairine appears at upper right (1905).

“Madame Breshkovskaya, who has struggled so long for the freedom of her country, wishes to struggle till the end of her days and I hope that some little remnant of her spirit will remain with us so that we, too may accomplish our freedom –the freedom to speak and act, not the freedom to starve in the streets. Then we may talk about American liberty, not before!”

De Cleyre most likely remembered that less than four years earlier when President McKinley was killed by a self-professed anarchist, Rev. Dr. Conwell had been one of the more extreme reactionaries when he declared in his Sunday sermon on September 16, 1901 that “a man who does not believe in our government is a tyrant to be destroyed by assassination, and has no right to be here… The very fact that he believes it is his duty to murder is sufficient evidence of his being a human tiger who has no right to live.” Russell Conwell, by the way, was the Baptist minister whose sudden about-face during a campaign against ballot-stuffing in municipal elections poisoned the appetite of a teen-aged Scott Nearing for organized religion for life, and Nearing lived to the age of one hundred.

The hardcore radicals present loved what Voltairine had done. She had set the idea of freedom straight and thrown the pompous hater of anarchists back into his box. But according to the Press reporter, Blackwell and the other middle class persons showed “great dissatisfaction,” and so did the Babushka herself.

In 2013 I was asked by a linguist named Kathy Ferguson to read the story that she suspected might have been penned by Voltairine de Cleyre, judging by the writing style. It is in Mother Earth vol 1, no 8 (October 1906). It is called “Between The Living And The Dead.” The story is unsigned, and appears on pages 58-61. This was an early issue of the leading anarchist journal in North America, and one of the best that has ever been published. However, no one seems ever to have reprinted it or commented on it. Kathy was examining the style and editing practices of the publication.

As I began reading the piece (either for the first time or the first in around 25 years), it felt like the hairs on my head were standing on end. It begins,

“We were three –a man, a child, and I who am a woman. It was in the winter and the man sat always at the front window of the third story opposite me, and the child in the parlor two stories below; and I from my second story saw them both. If they saw me, or seeing noticed me, I do not know, but I think they did: for we were kin, and the only kin in all that life that hurried round us, up and down, up and down. Ah, the long agony of those endless days, while we stayed watching the snow floating in the merciless atmosphere and the living people going up and down –we the unburied dead who from our coffin windows looked out!”

‘That’s her,’ I thought. I was already dead certain, because of the writing style. Then I started to consider when this was published, which is about eighteen months after Voltairine was confined in Medico-Chirurgical Hospital.

“And the child, ah well, the child with her ghastly face and sullen blue eyes, stared outward at the snow and the life that was all denied her; –such a young child, with the glory of youth still shining in her mass of pale hair.”

Voltairine spilled a lot of dark ink about starving, filthy children. I knew this one wasn’t headed for the Ivy League. A little farther on,

“”Ah, they too must die soon. The woman who sweeps the pavement there, impatient of the falling snow, she too must suffer; yet a little while she too must suffer and die. One day she will go in and close the door behind her, and never come out again. Those men who tramp so lustily, forcing back the cold and the snow with their hot hearts and limbs, they are tramping straight towards it, that last door which will open to them the fore-halls of death, wherein they, too, must sit unburied –long perhaps, like us. Ah, what is the use of it all? Why go up and down so? Why wait so long since the end is the same? Why not make an end? Why not make an end?””

Suicidal thinking. De Cleyre tried to kill herself at least twice.

“And the great hammer that beat in my head, the merciless hammer that rang like iron, began to clang: “And the sins….of the fathers….shall be visited….upon the children….unto the third….and the fourth….generation….And the sins….of the fathers….”

“I pressed my ears between my hands, but the hammer clanged on –“unto the third….and the fourth….generation.”….”

Not that I wasn’t already sure, but this is exactly the way Voltairine described her frequent migraines to her close friend Nathan Navro, as he wrote in an unpublished manuscript in the Joseph Ishill papers at Harvard. But “the sins of the fathers” is a time-worn code for venereal disease. If this were standing alone it would make me sure that she was the author, and it seals the matter of whether or not Voltairine suffered from syphilis. Further along,

“Under the hammer-clang repeating the pitiless law, my head reeled to and fro: “Oh Life, Life, where will you make it up to her? Why was the dream of justice ever born in the human mind, if it must stand dumb before this terrible child?”

“And far away there stretched before my eyes the limitless procession of little lives that had come forth in waste and blight, to die in their smitten youth, bearing through all their pain in the unnameable grace of babyhood, the aroma of green tendrils, the gloss of the down of childhood shining and floating still among the dust and death. Oh, that girl’s long golden hair! How thick and fair it gleams around the waxy face! And the little starved kitten in the alleyway with its delicate paws catching at a wind-blown straw! GOD? Did men ever believe a God could so order life? Did anyone ever believe it?”

Voltairine the burned-out, forty year-old social activist (which she was). Voltairine the atheist!

“We have gone from each other now. Somehow the door of my coffin reopened, and I came back to the living. The man passed down to the dead. Of his will he went. It happened so: on a day of thunder he leaned out and measured with his eyes for the last time; then he looked back into the room; no one was there. He set the geranium carefully at the side of the window-sill, and plunged to the stone below –the kind, hard stone that was merciful to him.”

As in Voltairine’s life, the narrator recovers and has left the hospital. The man jumping to his sad end is her usual gloomy scene, again in suicidal language. Farther down, the story ends,

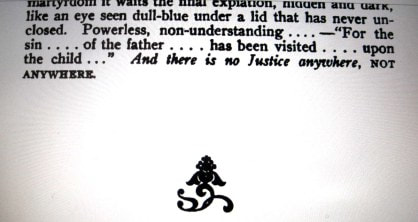

“Locked within the fatal narrowing circle, her soul is freezing while her body rots. Powerless in its martyrdom it waits the final expiation, hidden and dark, like an eye seen dull blue under a lid that has never unclosed. Powerless, non-understanding…. –“For the sin….of the father….has been visited….upon the child….” And there is no Justice anywhere, NOT ANYWHERE.”

Yes, that’s Voltairine de Cleyre all right. I’m so happy to discover this lost gem of hers, hidden in plain sight for over a century, that I might just go and hang myself. She could be the gloomiest person, and it’s no surprise she laid the despair on thickly, given the subject. This was de Cleyre’s agonized and deliberate statement to herself on a curse that she bore but could never discuss openly.

After reading the story and recognizing its authorship with the collaboration of Kathy Ferguson, the last and indisputable proof followed the end of the text, and for a little while, I was the only person on this wide Earth who could see it. I can hardly explain how much I enjoy moments like this.

Mother Earth, like many periodicals of its time, used random objects like a potted plant or a bird, or some symmetrical design that marked the place on a page where one piece ended and the next began. The object following “Between The Living And The Dead” is not a bird or a plant, nor is it symmetrical, and it floats in what would seem a needlessly large empty space on the page. Plenty of text could have fit there, but only the emblem is there.

De Cleyre most likely remembered that less than four years earlier when President McKinley was killed by a self-professed anarchist, Rev. Dr. Conwell had been one of the more extreme reactionaries when he declared in his Sunday sermon on September 16, 1901 that “a man who does not believe in our government is a tyrant to be destroyed by assassination, and has no right to be here… The very fact that he believes it is his duty to murder is sufficient evidence of his being a human tiger who has no right to live.” Russell Conwell, by the way, was the Baptist minister whose sudden about-face during a campaign against ballot-stuffing in municipal elections poisoned the appetite of a teen-aged Scott Nearing for organized religion for life, and Nearing lived to the age of one hundred.

The hardcore radicals present loved what Voltairine had done. She had set the idea of freedom straight and thrown the pompous hater of anarchists back into his box. But according to the Press reporter, Blackwell and the other middle class persons showed “great dissatisfaction,” and so did the Babushka herself.

In 2013 I was asked by a linguist named Kathy Ferguson to read the story that she suspected might have been penned by Voltairine de Cleyre, judging by the writing style. It is in Mother Earth vol 1, no 8 (October 1906). It is called “Between The Living And The Dead.” The story is unsigned, and appears on pages 58-61. This was an early issue of the leading anarchist journal in North America, and one of the best that has ever been published. However, no one seems ever to have reprinted it or commented on it. Kathy was examining the style and editing practices of the publication.

As I began reading the piece (either for the first time or the first in around 25 years), it felt like the hairs on my head were standing on end. It begins,